The Many Lives of Marguerite Ickis

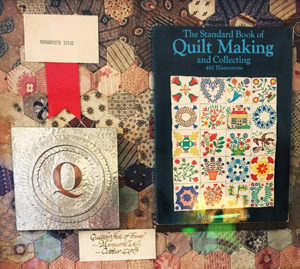

Marquerite Ickis gave us our first endowment along with her collection of paintings and books.

Born in 1896, she was a woman who was a pioneer and pathfinder: an editor, dean, researcher, the author of 20 books, a restaurateur, quilt designer and painter. Her work, The Standard Book of Quilt Making and Collecting, first published in 1949, remains the “how to” bible for quilters, reprinted several times and still selling today. One of the proudest moments in Marguerite’s adventurous life came in1979 (just a year before her death) when she was inducted into The Quilters Hall of Fame. She got up before the audience and began to tell them that she had lived “nine lives.”

And so her ninth life began—here in Dennis—in an old farmhouse at 112 Whig Street. She was sixty years old and attempted her first painting after almost going blind. When Marguerite could see colors again, she told a friend and artist who was helping her recuperate, “I would like to paint. She fixed my easel and mixed my paints, and upon seeing my first still life of flowers, declared unequivocally that I was going to be an artist.” (“Dennis Author-Painter Still Lives Valiantly,” Women’s World, 1978). This ninth life as a painter brought her back to her childhood in Ohio and it was through paint that she captured the stories of the little school house, the milliner’s shop, the dressmaker and the games of blind man’s bluff at the turn of the 20th century.

Marguerite was a writer long before becoming a painter. At a time when few women went to college, she received a master’s degree in Botany from Columbia University. Her many books on such topics as Handicrafts and Hobbies or The Book of Festivals and Holidays the World Over suggest someone who was fascinated by history, religious rituals and the arts and crafts movements of both the East and West. She was not only a researcher but a “maker of things,” a skilled quilter who taught quilting on the Cape many years after writing the definitive book. Even as Marguerite developed from an artisan to artist over the last twenty-three years of her life, quilting was her first love. As she put it that night at the Quilters Hall of Fame, “the quilting party is still going on!” She was 83.

Painting was another life and another story, not completely known or celebrated, except for her close circle of friends and fellow artists on the Cape. She often told visitors to the farmhouse that she went back in memory to create what she called “Vignettes of Marguerite” and “Children’s Games,” in the vibrant, colorful scenes that some have defined as folk art, reminiscent of Grandma Moses. When speaking of her painting, “Burying a Pet,” Marguerite wants her viewer to know, “it is a painting of mind and memory scenes that gave me an opportunity to sort out my life when I was blind.” In the 1940s she wrestled with “impending blindness from cataracts.” As she spoke of those difficult years, she recalled the words of a doctor: ” ‘if you look in your eyes as I just have you’d see beautiful waterfalls. That’s why the Greeks called them cataracts.’ It was the last description that helped me accept what was to come.”

She was going blind after writing 20 books. In “another life,” she had been the Dean of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) recreation school in the 1930s, heading up the national offices of the Girl Scouts of America. Undoubtedly, Marguerite met and knew Eleanor Roosevelt during these experimental and progressive years for women. Because of her formidable work with the WPA, she was asked to create the Institute of Recreation at the Teachers’ College of Columbia University. But, by the 1950s, Marguerite could no longer see well enough to grade her student papers. As she told friends, she could not walk down the Manhattan streets “without stumbling” and “was tired of watching soap operas.”

So she headed to her pre-Civil War farmhouse on Whig Street in Dennis and opened a small restaurant called the County Fair with just enough eyesight to “measure 3 cups of flour and 1 cup of lard for a pastry shell.” The first year, she had no money for stoves. “My building had been a storehouse for clipper ships on the Dennis shore and had been moved to Main Street. There was a stall in it which housed a horse and it certainly smelled terribly. We used grills. I had no screens. And do you know the Rockfellers, Fleischmans and others of that ilk came often and loved it.” (“Dennis Author-Painter Still Lives Valiantly,” Women’s World, 1978). The County Fair is now the location of the well-known, Red Pheasant restaurant.

Fifteen years passed—Marguerite was able to buy stoves and screens and build a well-loved gathering place where people came to eat, talk about art and see an occasional Broadway star. Most life-changing during these restaurant years, was the cataract operation that gave her back her eyesight; and so the painter was born at ago 60. ” I went back in memory to the sheep farm in Ohio where I was born.” For the remainder of her long life, Marguerite painted, quilted and continued to write. At 83, she was working on a book about the drummer boys of the Civil War. A photo taken of her in this last year of life shows a still serious-minded scholar, delving into a research book with her 1940s quilt draped over her shoulders—a quilt made from scraps gathered during the WPA theater project she worked on.

Marguerite was discovering more stories of the drummer boys when she passed in the summer of 1980 in Dennis. One of the last stories she uncovered was of the drummer boy who was beside Custer at the Battle of Little Big Horn.

Marguerite’s paintings now hang in a room with a fireplace and tall bookshelves, known as “The Ickis Room” of the Dennis Senior Center the Friends built. If you would like to view her paintings, please call our office for a private tour.

-Written by Marie Jainchill